The Airlift!

The Decision

On Monday 28 June 1948, faced with the reality of the Soviet blockade of Berlin President Truman called in several key cabinet members in the hope of clarifying the issue in his own mind. Plumbing the depth of their committment he listened as each in turn, Defense of Secretary James Forrestal, Secretary of the Army Kenneth Royall, and Undersecretary of State Robert Lovett all opined that the idea of an airlift should be discounted as a viable option. Withdrawal from the city seemed to be the only viable option. After a moment of consideration the President stated simply in a determined voice, "We stay in Berlin. Period."1 The die was cast.

Lucius Clay

GEN Lucius Clay was a decendant of statesman Henry Clay. Image Source: German Historical Institute, Washington, DC.

Several days earlier just as the blockade fell into place, General Lucius Clay, the American Military Governor in Germany offered his opinion to Army Secretary Royall that, "It seems important to decide just how far we will go short of war to stay in Berlin. We here think it extremely important to stay."2 When the matter of safety for military and diplomatic families arose in May 1948 as tensions increased, Clay who understood his responsibilities commented:

The evacuation of family members from Berlin would lead to a hysterical reaction and drive the Germans in droves into the supposed safety of Communism...We must not destroy their confidence by any indication of departure from Berlin.3

General Clay, an experienced leader who possessed common sense and determination had President Truman's confidence. His estimate of the situation on the ground was critical to the decision to remain in Berlin and weather the consequences.

Diplomatic Channels, Secret Conversations

Throughout the entire period of the blockade the Western Allies petitioned the Soviets through diplomatic channels to seek a solution that was amenable to both sides. On 6 July 1948 Secretary of State George Marshall contacted the Soviet Ambassador protesting that "the United States Government regards these measures of blockade as a clear violation of existing agreements concerning the administration of Berlin."4 That petition was made against the obvious Soviet move to control the city which was by treaty to be administered by the four occupying powers. In the background secret conversations occurred as each side tried to understand the full impact of the blockade and weigh the outcomes. The Central Intelligence Agency, under Director Admiral Robert Hillenkotter, continued to keep President Truman informed by keeping its finger on the pulse of Soviet activity and sharing with him their suspicions.

In confidential forums the Soviets registered their concerns and considered their options, especially when they realized they might have acted prematurely. In a meeting with Eastern Zone industrialists Marshal Sokolovsky registered amazement when he was informed that the blockade meant a number of operations would shut down from a lack of raw materials imported from the West including the steel industry. He noted that the only choices appeared to be: start a war, lift travel restrictions on Berlin, or leave Berlin entirely to the West. These would be all be weighed carefully as the West began the airlift in earnest.

Operation Vittles Takes Off

Tons of milk were flown into Berlin. Eventually condensed milk would be used to save space and weight. Image Source: German Historical Institute, Washington, DC.

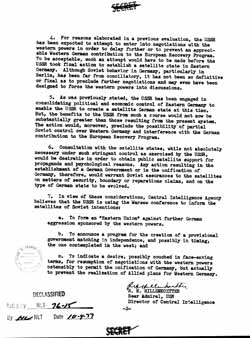

General Clay, with approval of the President, gave the order to initiate "Operation Vittles" on 25 June 1948. Within a day 32 C-47 'Skytrains' of the US Airforce departed carrying 80 tons of cargo which included medicine, milk, and flour for the relief of Berlin. By 28 June British aircraft would join the airbridge as would others from France and Canada, as well as aircrews from Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa. Initially C-47s shouldered the burden but their cargo capacity of only 3.5 tons made augmentation necessary by larger aircraft such as the C-54 'Skytrain'. By the end of August 1948 more than 1,500 flights a day were delivering over 4,500 tons of needed supplies. By September all the C-47s were replaced by US Airforce and US Navy C-54s which improved the cargo capacity to 5,000 tons daily. As the winter of 1948 approached cargo loads included more coal, necessary for heating. This raised the total daily requirement to 6,000 tons. To accomodate the increased number of flights and aircraft an additional asphalt runway was added at Tempelhof. The French also contributed by constructing a new airfield at Lake Tegel in their sector, to help manage the added air traffic. The western Allies resolve was being proven.

Around the Clock

Initial challenges like properly maintaining the aircraft, adequately employing aircrews, necessary record-keeping, and controlling the media had to be overcome. In time efficiencies were found that improved the process. This included bringing refreshments out to the aircrews on the flight line to save turn-around time and utilizing German workers as ground crews to assist in unloading cargoes. Because the operation ran continuously pilots operated under great strain often without adequate sleep. August 13, 1948 came to be known as "Black Friday" after three C-54 aircraft crashed during landings at Tempelhof in Berlin. As a result the Commander, Major General William H. Turner instituted mandatory changes such as mandatory instrument flight rules (IFR) that improved the safety of the operation.

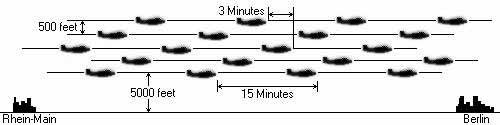

Soviet Interference

The Soviets could control the roads and rail, but failed to control the air corridors. Image by Leslie Illington. Source: National Library of Wales.

Initially the Soviets ridiculed the Western Allies' plan to initiate the airlift and challenged their resolve. In radio broadcasts to West Berlin they claimed rights to the entire city. They also predicted that it would eventually be surrendered to them and tempted West Berliners to cross to the East to receive food. This offer was refused by all. As the 'airbridge' increased in effectiveness and efficiency and Allied resolve seemed to strengthen the Soviets employed other means such as intereference by shining searchlights to blind pilots at night, buzzing by Soviet aircraft, air to air fire, firing of rockets and anti-aircraft guns, and parachute jumps into air corridors. None of these attempts were effective and instances eventually dropped off as the airlift continued into 1949.

Airlift Success

The airlift continued through to 15 April 1949 when a report by Tass, the Soviet News agency, announced a willingness to concede and raise the blockade. Negotiations among the four occupying powers followed and on 4 May 1949 the Allies agreed to end the blockade and curtail the airlift by 12 May. Immediately afterward a British convoy traveled by land route to the beleagured city and the first train from the West in nearly a year reached Berlin by early morning that day. A lessening volume of cargo flights continued for several more months until city stockpiles again reached an acceptable level as a safeguard against possible future blockades. In the final analysis statistics from the US Army Center for Military History record that the western Allies provided 714,090 short tons (STON) of supplies in 1948 and 1,198,305 STON in 1949. The total estimated cost was $224 million ($2 billion in 2008 dollars). The human toll was more dear with the loss of 40 British and 31 American servicemen who gave their lives to sustain those of over 2 million Berliners in the city and to demonstrate the Western will to maintain freedom in the shadow of a growing Soviet hegemony.